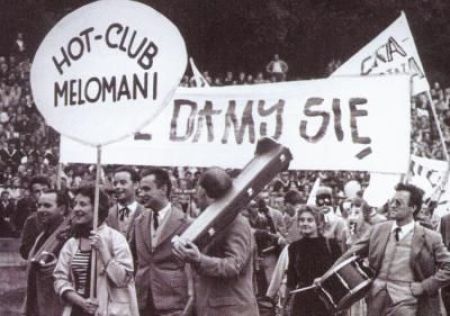

Many critics describe pianist and composer Krzysztof Komeda as the most important, popular, and influential Polish avant-garde jazz musician in history. Komeda was born in 1931, and started learning piano at a very young age during what was considered the romantic, or “catacomb” period of Polish jazz. Komeda was not his real surname, as he used the name as a pseudonym to separate his artistic life from his day job at a clinic. He began to participate in many be-bop and dixieland jazz jam sessions with other notable jazz musicians, such as Jerzy Grzewinski and 'Ptaszyn' Wroblewski. Eventually, Komeda helped form the Melomani jazz collective in 1947. This was a very influential group because they helped jazz thrive in the underground during its period of being banned under Stalin’s rule. After the ban was lifted, they also played popular jazz covers on the radio. The group made a notable performance at the Sopot Jazz Festival, one of the first landmark events in the history of Polish jazz after its initial ban (Radlinski).

Komeda’s jazz band usually performed as a quintet or sextet. The Komeda Sextet became the first Polish group to exclusively play a modern form of jazz that was almost completely separated from the traditional dixieland style. In 1966, the Komeda Quintet released their only proper studio album, Astigmatic. The album was marked by its intensely technical and avant-garde song styles. The album pioneered a markedly European aesthetic for jazz that did not merely copy American artists. Astigmatic was considered a significant milestone for Polish jazz, and is considered by many to be the greatest in its genre. It consists of 3 long tracks, “Astigmatic”, “Kattorna”, and “Svantetic”. The sound of the album is dominated by its rapid improvisational melodies. The instrumentalists use their own styles and imaginations as they continue to play new melodies and scales, each of them adding their own personal flair to the recording. However, Komeda’s formal compositional elements can also be inferred while listening to the album; the instrumentalists know when to play together softly, or when to start building up the intensity. Komeda also gives each member of the quintet a chance to perform their own solos. Aside from improvisations, there are also moments of carefully planned harmony between band members. An example is a passionate saxophone solo that makes up the middle section of the title track “Astigmatic”. This section is followed by a sparse, tense, emotionally ambiguous double bass solo. A rhythmic drum solo follows, and then the whole band comes back together to end the song. While one album may seem like not enough for Komeda to be such an influential musician, he was also recognized for his live performances, collaborations, and prolific amounts of Polish film scores (Radlinski).

The second most influential Polish avant-garde jazz pianist and composer was Andrzej Trzaskowski. He began his career in 1951 by joining the Melomani collective with Krzysztof Komeda. Later in the decade, he also helped form the jazz groups Jazz Believers and The Wreckers. Trzaskowski and his band also performed live in America and East and West Germany. Through these travels, he became inspired by the musical styles of other cultures, and decided to combine elements of their music with the evolving scene of Polish jazz. Trzaskowski’s music was best known for its fusion of Polish jazz and western classical music. This type of avant-garde jazz came to be known as third stream. His music blended serious, traditional styles with contemporary techniques of composition. His compositions also became more avant-garde as time went on (Slawinski, Culture.pl).

The most popular album by the Andrzej Trzaskowski Quintet was their self-titled album. It was also known as Polish Jazz Volume 4. Polish Jazz was a prestigious label that ran from 1965 to 1989, which also published Komeda’s Astigmatic. The Andrzej Trzaskowski Quintet features piano, double bass, trumpet, saxophone, and drums. The album often builds up an atmosphere of suspense, which transitions into loud and chaotic instrumental solos. The eclectic album also has quite a bit of variety in song structures and emotional content. The opening song, “Requiem dla Scotta La Faro”, starts with a mysterious, occasionally dissonant piano. The piano chords are sparse, and the bouts of playing have long silences between them. Each time the piano comes back, the music builds in intensity until all the band members are playing together loudly; this is followed by a collapse back down into the pattern of quiet, sparse, dark piano. The following 18-minute abstract track “Synopsis” uses similar elements of suspense and chaos, with more lengthy and melodic instrumental solos on the double bass and horn instruments. In contrast, the songs “Ballada z silverowską kadencją” and “Post Scriptum” are shorter and subtler, laid-back and relaxed piano-based melodies (Slawinski).

Komeda’s compositions and Trzaskowski’s recordings represent how two different approaches to the jazz genre both represented the same anti-Soviet ideal. Komeda’s pioneering of a distinctively Polish aesthetic for jazz helped rebel against the oppressive Soviet communist culture that was being pushed by the government. Other musicians who incorporated elements of Polish folk into their jazz compositions helped create a sense of national pride to help people stand together during the revolutions of the Cold War. Trzaskowski’s approach was to blend classical western elements into his jazz compositions, which served nearly the same purpose. The third stream subculture of Polish jazz was one of many examples of the diffusion of Western culture to the East, which stood against a government trying to paint the West as a capitalist enemy.

After the 1960s, jazz continued to thrive, become more avant-garde, and play a strong role in the anti-communist counterculture of Poland. Jazz clubs and concerts could be a gathering place for artists and fans who were opposed to the actions of the state. The combination of multiple grassroots anti-state cultural phenomena, such as that of jazz, ultimately led to the fall of communism in Poland in 1989. Jazz was not the main cause of the fall, but it was certainly a major catalyst. However, with the fall of communism and the rise of capitalism, jazz was losing steam; its avant-garde nature had no commercial value, and Polish audiences were mostly interested in Western-style pop. Despite this, some obscure but passionate experimental subcultures still formed. A new Polish avant-garde jazz movement known as yass arose in the 1990s; this movement was even more eclectic than the initial wave of jazz. Yass included influences of Polish punk and folk, and could be more eccentric and experimental. Even though Polish avant-garde jazz today is an esoteric underground subculture, the influence of the early works in the genre are deeply appreciated; the love for the works of Komeda and Trzaskowski continue to this day.

Works Cited

Culture.pl. Polish Jazz - Freedom at Last. Culture.pl, Adam Mickiewicz Institute, 19 January 2009, https://culture.pl/en/article/polish-jazz-freedom-at-last Accessed 21 February 2021.

InterContinental. Forbidden Bebop: How Eastern European Jazz Keeps Breaking All the Rules. InterContinental, IHG, n.d., https://life.intercontinental.com/sg/empathy-sg/forbidden-bebop-how-eastern-european-jazz-keeps-breaking-all-the-rules/ Accessed 21 February 2021.

Jakelski, Lisa. Gorecki’s Scontri and Avant-Garde Music in Cold War Poland. The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 26, No. 2, University of California Press, Spring 2009, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jm.2009.26.2.205?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents Accessed 21 February 2021.

Radlinski, Jerzy. Christopher Komeda (1931-1969). Komeda.pl, n.d., https://www.komeda.pl/indexa.html Accessed 21 February 2021.

Slawinski, Adam. The Andrzej Trzaskowski Quintet – Polish Jazz Vol. 4. Polish Jazz, Polish Jazz Net, 2005, https://web.archive.org/web/20070824220846/http://www.polishjazz.com/pjs/4.htm Accessed 21 February 2021.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1763330-1309765336.jpeg.jpg)